Many customers ask me how this product is made, it's actually not that complicated, really. I mean, when you look at a serum blood collection tube—those little clear vials with the colorful caps you see at the doctor’s office—you probably think there’s some wild science going on. And sure, the medical part is science, but the making of the tube? It’s just manufacturing. It’s heat, pressure, and timing. I’ve been around these factories for a long time, seen a lot of things go right and a lot of things go wrong, and honestly, making these plain tubes is one of the more straightforward jobs, provided you have the right gear.

It all starts with the plastic itself. Usually, for these tubes, we are talking about PET or maybe PP. It comes in these big bags of pellets, looks kind of like heavy rice or clear beads. Now, here is where people mess up. I’ve seen guys try to just dump that stuff straight into the machine. You can’t do that. Plastic acts like a sponge, believe it or not. It soaks up moisture from the air. If you try to melt wet plastic, you get bubbles. We call them silver streaks. It looks terrible, and for a medical product, "terrible" means "trash."

So, before anything fun happens, you have to dry the stuff. That’s where the **hopper dryer** comes in. It sits on top of the machine usually, just blowing hot air through the pellets for hours. It’s not exciting, but if you skip it, you’re done. I always tell people, the dryer is the most boring machine that you absolutely cannot live without.

Getting the plastic into the dryer used to be a back-breaking job. I remember years ago hauling sacks up ladders. Terrible for your knees. Now, too much everyone uses an "auto loader". It’s this vacuum thing that just sucks the pellets out of the bag and shoots them up into the hopper. It’s noisy, kind of a "woosh-clatter-clatter" sound, but it beats carrying fifty-pound bags all day.

Sometimes you need to add things to the plastic, though for plain serum tubes it’s usually just clear. But if you were doing the caps, or if the customer wanted a specific tint, you’d use a **mixer**. You throw the clear pellets in with the color masterbatch and let it tumble. It reminds me of those cement mixers you see on construction sites, just smaller and cleaner. If you don't mix it right, you get swirls. Nobody wants a swirly blood tube. It just looks unprofessional.

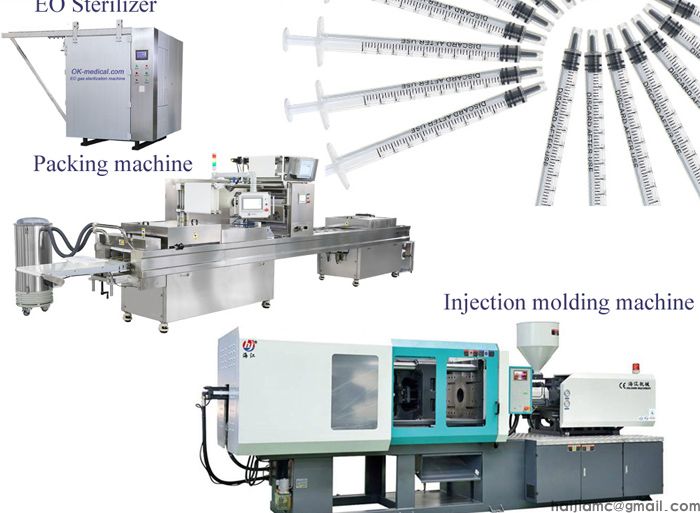

If the plastic is dry and ready, it goes into the belly of the beast: the **plastic injection molding machine**. This is the heart of the whole operation. It’s big, it iss loud, and it gives off a lot of heat. Inside the machine, there’s this giant screw that turns and pushes the plastic forward while heaters melt it down into a thick, sticky syrup. It has to be the exact right temperature too. If cold, and it won't fill the shape. Too hot, and the plastic burns. I’ve smelled burnt plastic more times than I care to admit—it smells like burning hair and chemicals. It sticks in your nose for days.

The machine shoots this hot, melted goo into the **mould**. Or **mold**, depending on how you like to spell it. I see it written both ways on the spec sheets. This is the most expensive part of the line. It’s a big block of steel that has the shape of the tubes carved into it. For these blood tubes, you usually have a mold with lots of cavities—maybe 32 or 48 tubes getting made at once. It clamps shut with tons of pressure. Literally tons. If it didn't clamp tight, the plastic would squirt out the sides, and you’d get what we call "flash." That’s those little sharp edges you sometimes feel on cheap plastic toys. In the medical world, flash is a no-go. You can’t have sharp bits on something a nurse is holding.

Now, you have hot plastic inside a steel block. It needs to turn back into a solid tube, and it needs to do it fast. Time is money, right? If you sit around waiting for it to cool down naturally, you’ll only make a few tubes a minute. That’s why you hook up a **chiller**. The chiller pumps cold water through channels inside the mold to down the heat out instantly. It’s a delicate balance. If you cool it too fast, the plastic can warp. If you cool it too slow, the cycle time is too long. I’ve spent hours just staring at the temperature gauges on a chiller, tweaking it by a degree here or there, trying to get it perfect.

When the mold opens, the tubes get pushed out. It’s actually kind of satisfying to watch. *Clunk-hiss-clatter*. A few dozen fresh, clear tubes drop down.

But hey, we aren't perfect. Sometimes things go wrong. Maybe the machine jammed, or the color was off, or the startup batch was just cold. You end up with a pile of bad tubes. In the old days, that might have been trash, but plastic is valuable. So, we use a **crusher**. It’s exactly what it sounds like. You throw the bad tubes in, and it grinds them back up into little chips. You can usually mix a little bit of that regrind back in with the fresh stuff. It saves money. Just don’t use too much, or the tubes start to look yellow.

It’s funny, when you hold one of these tubes in the hospital, you’re usually nervous about the needle or the blood draw. You never think about the guy who spent three hours fixing the auto loader because a piece of cardboard got stuck in the hose, or the time the chiller sprung a leak and flooded the shop floor. I’ve slipped on that water before—not fun.

The whole line just runs, *chug-chug-chug*, making thousands of these things a day. It’s a messy, loud, hot process to make something that looks so sterile and clean. But that’s manufacturing for you. It’s never as clean as the final product looks. I personally think there’s something kind of beautiful about it, though. Taking a bag of dusty pellets and turning it into something that helps save lives? That’s not a bad way to spend a Tuesday.

I wonder if doctors ever look at the tube and wonder where it came from? probably not. They have more important things to worry about. But next time you get blood drawn, take a look at the plastic. If it’s clear and smooth, you know the hopper dryer was working.